Collaborative Piano faculty Katherine Chu shares her journey on how she discovered and developed her passion for vocal music and opera coaching.

To this day, I still have trouble explaining to my loving, open-minded, and unconditionally supportive parents what I do in my profession. They used to ask, “What is it that you do?” To which I replied, “I am a vocal coach!” Their response: “Don’t you play the piano? We thought you teach piano to kids. Anyway, do you even know how to sing?” Why should my parents, born in the Chinese ghettos of colonial Vietnam, make the wild association between piano playing and vocal coaching?

I am most grateful to my parents for the opportunity to move to the United States at the age of 12. In the small town of York, Pennsylvania, I started piano lessons and enjoyed the freedom to seek out my own learning opportunities as well as develop my interests. At the tender age of 16, I fell in love with vocal music. The local voice teacher was looking for a pianist to accompany her studio lessons. I promptly applied and got the gig. This was my first exposure to the German language, poetry, and art songs. I found German Lieder so “deep and romantic” and vowed to learn German and play more art songs. Later, I was introduced to “Voi che sapete” from Le nozze di Figaro. I had no idea what the aria or the opera was about, but thought the music was just heavenly and sublime. From that point on, I knew what I wanted to pursue in life—collaborative piano, which is a specific field of expertise that encompasses many disciplines, of which I have chosen to focus on the coaching of vocal music and collaborating with vocalists.

Throughout my undergraduate studies in piano performance, I sought out opportunities to explore the fascinating world of vocal music by playing voice studio lessons, opera classes, and rehearsals. My first time playing for the school opera production was quite intimidating. Within one year, I got a preview of a coach’s “métier”: watching the conductor, playing the harpsichord continuo and celesta in the orchestra pit. Considering my lack of prior experience, it was kind of the opera department to pay me, even though I did not expect it.

At age 20, I auditioned for my first apprenticeship with the Chautauqua Opera. At the audition, the artistic director placed the Carmen quintet in front of me to sight-read. He gave me the tempo and off I went in a manic dash of five flats in sixteenth notes played to one beat per measure and five vocal lines to track, with occasional tempo changes and pauses in between as requested by the artistic director. When I came out at the other end, he said, “Well, you did not freak out, so you are hired!” With this, I took my first professional step toward a lifelong learning curve.

After that memorable summer at Chautauqua, I set up my own study goals in vocal music and opera coaching. I prioritized score reading, which was a one semester requirement in my undergraduate program, and language proficiency. I started playing for singers who were native speakers of other Indo-European languages in exchange for free tutoring. For me, proficiency in foreign languages is the key to studying vocal music of any kind. Studying vocal music, operas in particular, is like traveling through space and time. You can cross borders into another culture, country, historical period, or even mythical realm, through vocal music. What’s there not to like about this field? Virtual travel to anywhere you want!

One fine day in 1997, I received a call from an American impresario looking to hire a pianist fluent in Mandarin and Italian to be the répétiteur and chorus master for a production of Rigoletto in Beijing. It was my first visit to Beijing. During this production, I worked with Seiji Ozawa’s production and music education team. This led to my journey back to Asia where I started collaborating with Seiji a few years later.

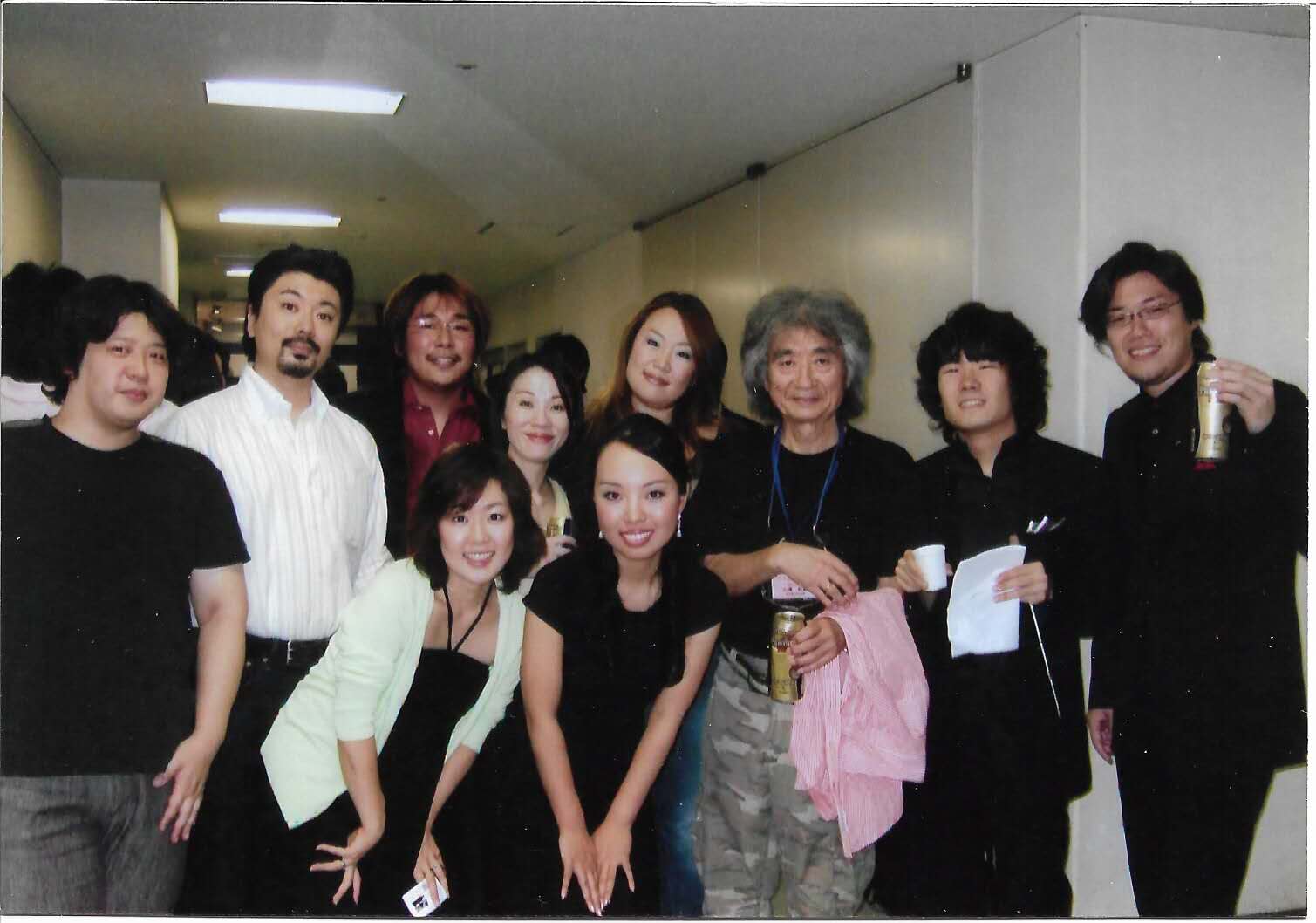

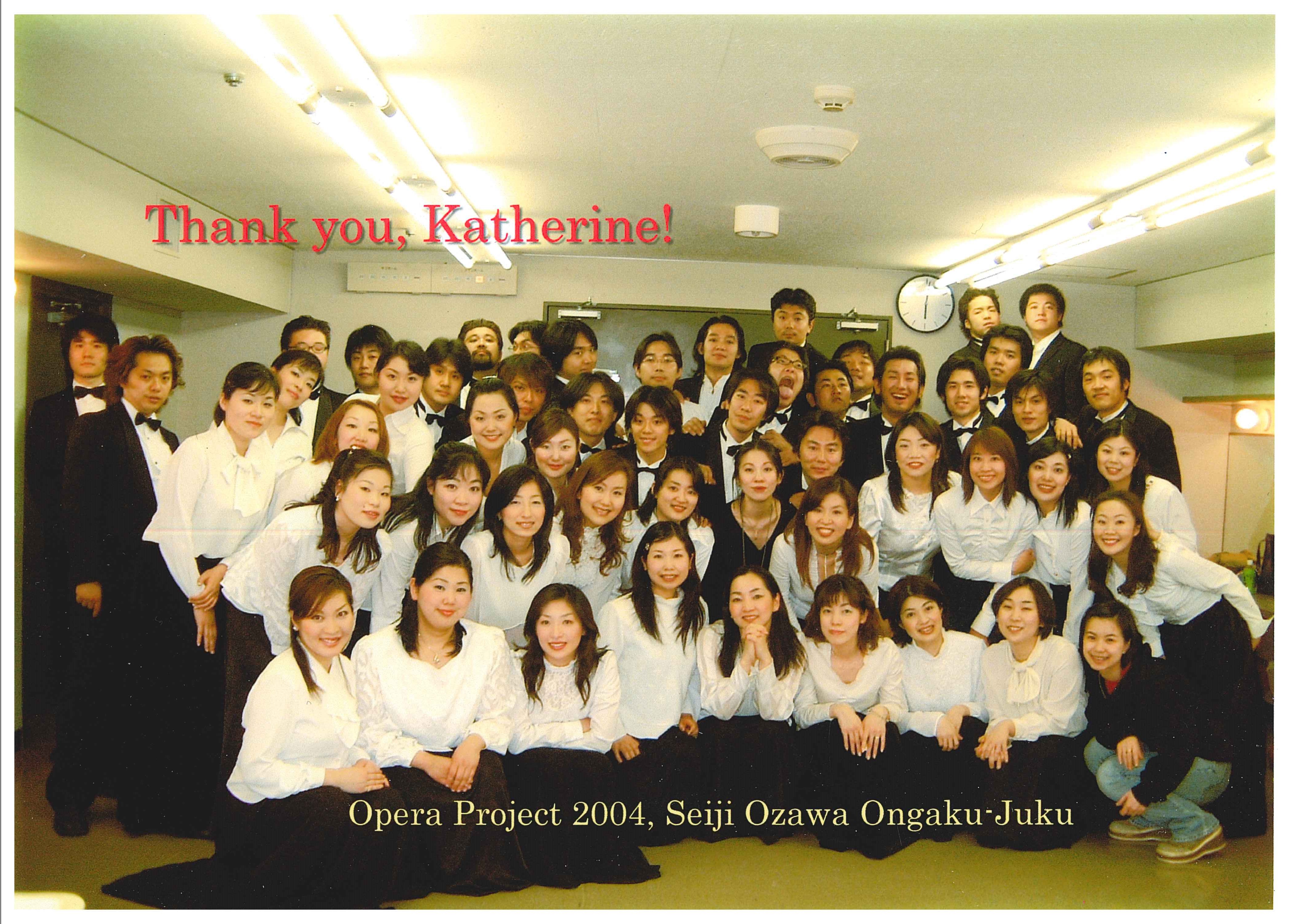

Working with Seiji was the one of the most exhilarating and fulfilling experiences in my life. Seiji firmly believed that chamber music was at the core of all music-making, and founded the Seiji Ozawa Music Academy, which was devoted to teaching the art of collaborative music-making to talented young Asian instrumentalists and singers. When it came to opera, which he adored, Seiji was a most dedicated and humble colleague. We introduced young musicians to worlds inhabited by characters from moral parables of the Enlightenment, gypsies’ tales of passion and doom, and farce in Viennese high society. Through Seiji’s efforts, I realized that musicians in Asia had superb technical training, but needed the cultural immersion in order to understand and reach the truth in music. The best ways to achieve this vision was through coaching at the highest level.

Seiji’s enterprise introduced me to the enormous potential for classical music and vocal talent in China. I began to guest-teach extensively in China and eventually joined the National Centre for the Performing Arts (NCPA) to help them build a production infrastructure. The 1990s was an exciting period of opening up for the arts in China. I accompanied China’s cultural development, growing up and blossoming throughout these years, first starting off as a young coach in the 90’s, and settling in China during the late 2000’s as a seasoned professional and teacher.As I trained young rehearsal pianists and worked with intern assistant conductors, I felt that while they excelled technically, they needed to build well-rounded knowledge of all related disciplines in opera, and an awareness of the collaborative nature of music-making in the theatre. I felt rewarded to see them full of curiosity and thirst for knowledge. Moreover, I felt grateful that my U.S. education allowed me to develop an affinity to languages and an appreciation for different artistic disciplines, which have in turn influenced my teaching and music-making.

I am convinced that students would benefit greatly from coaching rooted in a broader cultural preparation, and that their artistic growth is enriched by these forays into other disciplines. A few years ago, I was guest-teaching at the Shanghai Conservatory when I came upon a master class given by András Schiff. A young pianist played for him a fugue from Bach’s The Well-tempered Clavier. Schiff set the German text “es muss sein” to the notes of the motive and asked the pianist to “sing” these words as she played the motive with each fugal entry. Immediately, there was breath, space, and timing in her phrasing. Even though the pianist might not have understood the words, she was sensitive to the effect of language and started to hear the music in a different way. I was amazed by the transformation and fascinated by Schiff’s cross-disciplinary approach.

At present, there are many great opportunities for collaborative pianists because the field is wider and the needs are broader. Legendary string masters forged formidable partnerships with musical soulmates at the piano. The great Italian operatic “divi” and “dive” were coached syllable by syllable and phrase by phrase to obtain the most ravishing sounds and meaningful nuances by the “maestri collaboratori” of opera’s golden age. In looking at collaborative piano with a focus on vocal music, the skill set required for this field is diverse and wide-ranging. A vocal coach also needs to develop a sense of style, taste, and finesse about the vocal arts as a complex of traditions and practices. An early start is important, whether it is language acquisition, repertoire building, or experience accumulation—these are all aspects of our specialty that take time to attain and grow.

The study of vocal music and the experiences in opera have presented me with a cornucopia of inspired moments, stimulating ideas, and boundless beauty. In the 23 years that I spent in Asia, it has been deeply fulfilling to have introduced a collaborative way of experiencing music in China. Sharing in these young pianists’ joyous discovery of vocal music, I feel blessed to relive the thrill I had when I was awe-struck by its wonders, all those years ago.